In the quiet void between brushstrokes and forms, a powerful counterforce emerges: negative space. Often overlooked, this invisible backdrop is not merely empty canvas; it is an active participant in composition, guiding the eye, shaping emotion, and revealing the artist’s intent. As painters, sculptors, and photographers have discovered over centuries, the space that surrounds the subject can be as expressive as the subject itself. By studying how negative space interacts with light, color, and line, we gain a deeper understanding of how fine art communicates beyond its visible elements.

Historical Roots of Negative Space

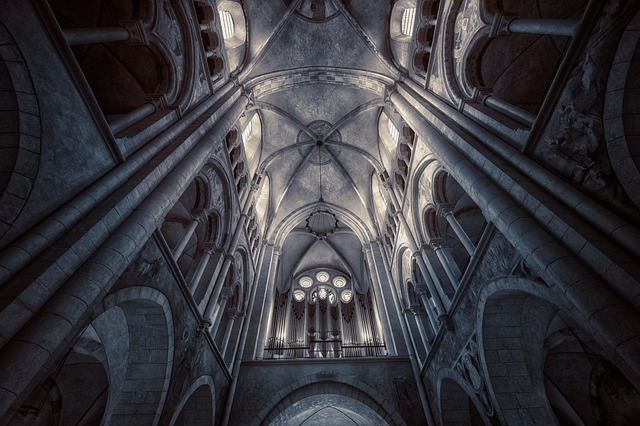

The concept of negative space has roots that stretch back to ancient art, where the simplicity of line and form often left deliberate voids to suggest depth or spiritual emptiness. In East Asian ink painting, the untouched areas of paper were intentionally kept blank to convey emptiness, balance, and the idea that what is not shown can be as potent as what is. Similarly, the early Islamic architectural mosaics used white marble as a negative backdrop to accentuate intricate geometric patterns, allowing the viewer’s imagination to fill in the gaps.

Western art history saw a transformation in the 19th and 20th centuries. Claude Monet’s impressionist brushwork created hazy clouds of color that, together with the spaces in between, captured the transient quality of light. The Bauhaus movement, especially in the works of artists like Josef Albers, embraced negative space to explore color interaction, teaching students how absence could illuminate presence. In sculpture, Auguste Rodin’s careful use of voids around his figures drew attention to the physicality of his subjects, turning the empty space into an integral part of the narrative.

Technical Foundations and Visual Language

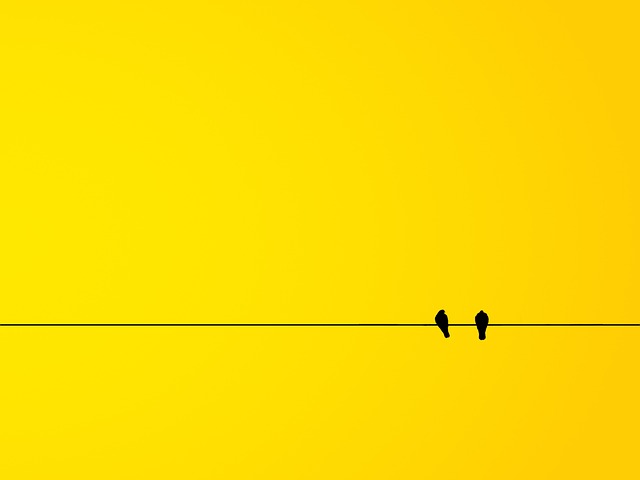

Negative space functions on several visual principles. Firstly, it establishes balance; when the viewer’s eye encounters a solid form, it naturally seeks equilibrium by looking toward the empty area. This symmetry creates a sense of stability, making the composition feel intentional rather than chaotic.

“The space around a form is as important as the form itself.” – Ansel Adams (though primarily a photographer, his quote underlines the universality of negative space across mediums)

Secondly, it provides contrast. A stark white background against a dark subject amplifies the subject’s silhouette, lending it power and drama. Conversely, a muted background can soften a bold figure, encouraging the viewer to focus on subtle details.

Finally, negative space invites imagination. By leaving areas unpainted, artists create a dialogue with the audience, allowing personal interpretation to fill in the gaps. This interplay between what is shown and what is left to the mind can transform a straightforward depiction into a layered, contemplative experience.

Case Studies: From Classic to Contemporary

- Albrecht Dürer’s “Melencolia I” – The figure is surrounded by a vast, empty sky that amplifies the contemplative mood.

- Henri Matisse’s “The Snail” – Vibrant colors are juxtaposed with a stark white canvas that frames the spiraling composition.

- Modernist photographer Richard Avedon – In portrait sessions, the absence of background distracts from the subject’s expression, focusing entirely on the face.

- Digital artist Refik Anadol’s immersive installations – He uses negative space within data-driven visuals to create breathing room for information, making complex patterns digestible.

Each example illustrates how negative space can be used strategically to influence perception, mood, and narrative. Whether through minimalistic design or richly textured backgrounds, the choice of void shapes the viewer’s journey across the artwork.

Interactive Applications in Contemporary Fine Art

Today, the dialogue between object and void extends into digital realms. Artists employ algorithmic processes to generate dynamic canvases where negative space evolves over time, reflecting social or environmental data. In these installations, the absence becomes a live entity, shifting in rhythm with the viewer’s movements or external stimuli.

- Projection Mapping – Large-scale murals project moving shapes that intermittently reveal or conceal parts of the surface, turning the surrounding space into a storytelling tool.

- Augmented Reality (AR) Paintings – By layering digital elements onto physical canvases, artists can create invisible borders that alter the perceived depth of a work.

- Eco-art Installations – Sculptures made of biodegradable materials are positioned against barren landscapes, letting nature itself act as the negative space that frames the temporary art.

These practices underscore how negative space is not static; it interacts with technology, environment, and audience engagement, continuously redefining the canvas in real time.

Teaching the Power of Negative Space

Educational programs across art schools emphasize the importance of negative space from the earliest stages of learning. By asking students to paint a single object against a white backdrop, instructors highlight how the empty area informs the subject’s form. Subsequent exercises involve layering multiple objects, encouraging learners to negotiate spatial relationships and understand how overlapping forms change the surrounding void.

Critique sessions often revolve around how effectively students manipulate negative space to create harmony or tension. In digital illustration workshops, designers learn to use layers and masks to isolate or merge negative zones, providing a practical toolkit for modern media. These pedagogical strategies ensure that emerging artists recognize negative space as an indispensable element of compositional design, rather than a mere afterthought.

Conclusion: The Canvas as a Dialogue

Negative space is more than absence; it is a dynamic partner in storytelling. By engaging with voids, artists craft canvases that are balanced, evocative, and open to interpretation. Whether in the measured strokes of a Renaissance master or the algorithmically generated forms of a contemporary digital artist, the interplay of presence and absence shapes the viewer’s experience.

As we continue to explore new mediums and technologies, the principle remains constant: the canvas is not only what is painted or sculpted but also what is left unfilled. In embracing the power of negative space, fine art redefines itself, inviting audiences into a conversation where every empty square is as meaningful as every filled one.