Perspective, a term that immediately evokes the sense of depth and spatial illusion, sits at the heart of visual storytelling in fine arts. It is not merely a technical device but a cultural lens through which artists translate three‑dimensional reality onto a two‑dimensional plane. The way perspective is employed, challenged, or abandoned reveals much about the societies that produce the works and the personal philosophies of the creators themselves. In this exploration, we trace how perspective has evolved across epochs, examine its diverse cultural interpretations, and consider how contemporary practices continue to redefine what it means to “see” art.

From Linear to Atmospheric: The Evolution of Perspective

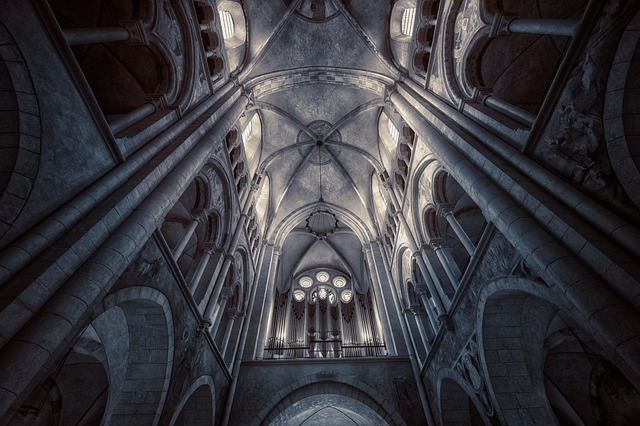

The formal study of linear perspective emerged in the Italian Renaissance, largely attributed to Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti. Their work established a mathematical framework that allowed painters to depict a realistic spatial arrangement by converging orthogonal lines toward a single vanishing point. This breakthrough empowered artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Titian to create immersive scenes that guided the viewer’s eye into the painted world. The subsequent spread of this technique across Europe set a canon that would dominate Western art for centuries.

However, as time progressed, artists began to question the rigidity of linear rules. The Baroque period introduced a more dynamic perspective, with multiple vanishing points and dramatic viewpoints that heighted emotional impact. Later, the 19th‑century Impressionists, led by Monet and Renoir, favored a fragmented, almost flat approach that downplayed depth in favor of light and color. The 20th century saw a further break: Cubists like Picasso deconstructed perspective entirely, representing objects from simultaneous angles and rejecting the idea of a single, objective viewpoint.

Perspective in Non‑Western Traditions

While the linear model dominated in Europe, other cultures developed distinct approaches to spatial representation. In East Asian art, especially within Chinese ink painting and Japanese ukiyo‑e, a sense of depth is achieved through layering, atmospheric haze, and the careful use of negative space rather than strict geometric rules. The “depth of field” in these works guides the viewer’s gaze organically, inviting contemplation rather than a voyeuristic immersion.

“In Japanese aesthetics, the idea of perspective is less about drawing a straight line and more about creating a feeling of space that encourages the viewer to explore the unseen.” — Anonymous

In African and Indigenous art, perspective often serves symbolic rather than realist functions. The depiction of cosmological narratives, spiritual beings, or communal rituals uses spatial manipulation to encode meaning. A single focal point may represent a sacred center, while the surrounding space expands outward, creating a metaphysical rather than a physical depth. These practices demonstrate that perspective can be a cultural signifier, embodying values that transcend the mere portrayal of three‑dimensionality.

Technical Practices: Tools, Mediums, and Methodology

Artists manipulate perspective through a combination of tools, materials, and conceptual choices. Traditional techniques include the use of vanishing points, foreshortening, and the manipulation of scale. Modern artists, meanwhile, might employ digital software that allows for virtual 3D modeling, enabling a more literal rendering of space or, conversely, the creation of entirely surreal environments that challenge conventional perspective.

- Linear perspective: Converging lines, single or multiple vanishing points.

- Atmospheric perspective: Gradual changes in color, contrast, and clarity to suggest distance.

- Foreshortening: Distortion of objects to indicate their proximity or receding motion.

- Virtual reality: Immersive 3D spaces that alter the viewer’s sense of direction.

The choice of medium—oil, watercolor, charcoal, or digital—also dictates how perspective can be expressed. For instance, the slow drying time of oil paint allows for subtle blending that can create gradual depth, while the immediacy of charcoal can produce stark, dramatic contrasts that draw attention to specific focal points. Each medium invites different approaches to the perception of space.

Case Studies: Artists Who Redefined Perspective

Vincent van Gogh manipulated perspective to convey emotional intensity. His swirling brushstrokes and vibrant color palettes often collapsed depth into a flat, expressive field, challenging viewers to interpret meaning beyond spatial accuracy.

Mark Rothko embraced a near‑flat approach, using large fields of color that create a meditative sense of space. The viewer is invited to feel the colors rather than to trace spatial relations.

Yayoi Kusama incorporates repetitive patterns and infinity mirrors to dissolve conventional perspective, creating environments where depth is both suggested and negated, encouraging a contemplation of endlessness and self.

- Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” demonstrates how emotional content can override geometric accuracy.

- Rothko’s “No. 61 (Brown, Black, Orange, Red & Yellow)” invites viewers to experience color as space.

- Kusama’s “Infinity Mirror Room” dissolves boundaries, offering a different take on depth.

Perspective in Contemporary Cultural Dialogue

Today’s globalized art world engages with perspective as a dialogue about identity, representation, and power. In a digital age, where images can be instantly altered and disseminated worldwide, artists are questioning the authenticity of visual truth. The concept of perspective extends into media studies, where the framing of narratives—whether through photographs, films, or social media—determines which stories are visible and which are marginalized.

Contemporary installations often use mixed media and interactive technology to give viewers agency in how they perceive space. Artists like Olafur Eliasson construct immersive environments that respond to the viewer’s movement, making the act of observation itself part of the artwork. This interactive perspective challenges static viewpoints and encourages a more democratic engagement with visual culture.

Future Directions: Technological Integration and Societal Impact

Emerging technologies such as augmented reality (AR) and artificial intelligence (AI) are poised to redefine perspective further. AR overlays digital layers onto real environments, creating hybrid spaces where the real and the virtual intersect. AI can generate photorealistic scenes or manipulate existing works to explore alternate viewpoints, prompting questions about authorship and authenticity.

The integration of these technologies invites artists to consider how perspective can serve social justice. By reconstructing visual narratives that include historically excluded viewpoints, new works can broaden the collective understanding of space and place. For example, virtual reconstructions of lost cultural sites enable communities to reclaim heritage and visualize cultural memory in new dimensions.

Conclusion: Perspective as a Living, Cultural Practice

Perspective in fine arts is more than a technical skill; it is a living, evolving practice that reflects cultural values, technological advancements, and philosophical inquiries. From the precise lines of the Renaissance to the abstract fields of contemporary abstraction, perspective continues to be a conduit for artists to negotiate reality, imagination, and identity. As we look toward the future, the ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation promises to expand the ways in which we perceive, represent, and ultimately understand the spaces we inhabit.